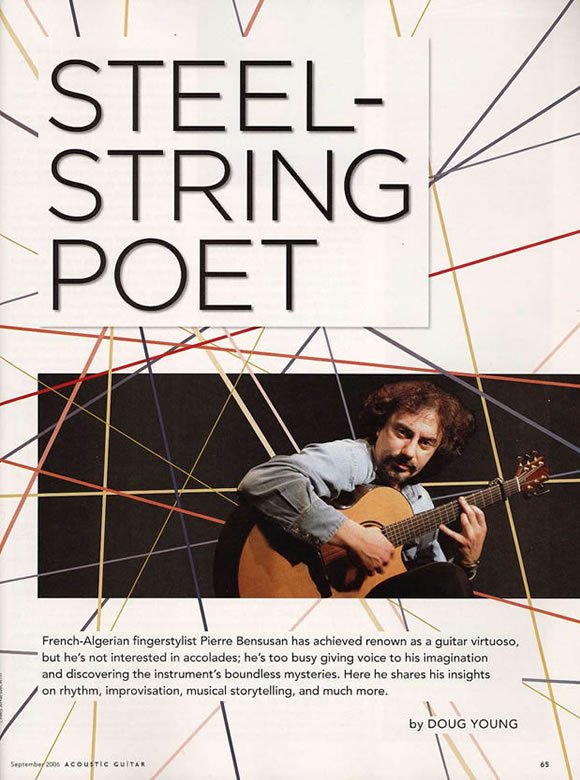

STEEL-STRING POET

French-Algerian fingerstylist Pierre Bensusan has achieved renown as a guitar virtuoso, but he’s not interested in accolades; he’s too busy giving voice to his imagination and discovering the instrument’s boundless mysteries. Here he shares his insights on rhythm, improvisation, musical storytelling, and much more.

By DOUG YOUNG

Pierre Bensusan is one of those rare musicians who can communicate his inner musical voice in a way that transcends his instrument. Bensusan’s compositions often start with melodies inspired by various folk traditions. But he develops these ideas into compositions of astonishing complexity, creating beautiful and sensuous sounds with a sense of orchestration that goes far beyond what is generally thought of as guitar music. His pieces commonly feature syncopated rhythms, unusual time signatures, and complex harmonic structures. Any guitarist who has tried to learn one of his tunes will attest to the technical challenges presented by his music. Yet mastering difficult fingerings is never the point; what interests Bensusan is the greater challenge of creating the artful statements that seems to flow effortlessly from his guitar.

Born in French Algeria in 1957, Bensusan moved as a child with his family to Paris, where he initially studied classical piano before switching to the guitar at age 11. Although he acknowledges everyone from John Renbourn to Joni Mitchell and even Jimi Hendrix among his influences, Pierre quickly developed his own sound. His early albums—he recorded his debut, Pres de Paris (Rounder Records), at age 17—demonstrate a strong folk and Celtic influence, but also present a stylistic approach that is uniquely Pierre. Over more than 30 years, his music has constantly evolved, incorporating elements of jazz, Latin, Middle Eastern and North African music, along with classical and impressionistic influences, into a seamless blend that defies categorization.

The 2001 album Intuite (Favored Nations) presented Bensusan’s guitar for the first time in a completely solo setting. Dazzling in both its virtuosity and lyricism, Intuite was honored as album of the year by a number of critics. His most recent recording, 2005’s Altiplanos (Favored Nations), marked a return to occasional vocals and backing instruments, and included several marvelous compositions that reveal more and more with each listening.

Bensusan goes to great lengths to share his knowledge with other guitarists. His first book, titled simply The Guitar Book (Hal Leonard, 1986), has become a classic, with its unique blend of exercises, music, poetry, and recipes for some of his favorite foods; since its publication, painstakingly accurate tablature has become available for many of his compositions, including all of the music on Intuite and most of Altiplanos. A few years ago, Stefan Grossman’s Guitar Workshop released The Guitar of Pierre Bensusan, a two-volume instructional video in which he deconstructs his style in great detail. Bensusan gives seminars and master classes all over the world and hosts a residential seminar for intermediate to advanced guitarists each summer in his home in France. (For more information on Bensusan's work, see Pierre Bensusan's website.) An acknowledged master of D A D G A D tuning, he frequently points out that D A D G A D is a tool, not an objective, and teaches that music is about more than alternate tunings.

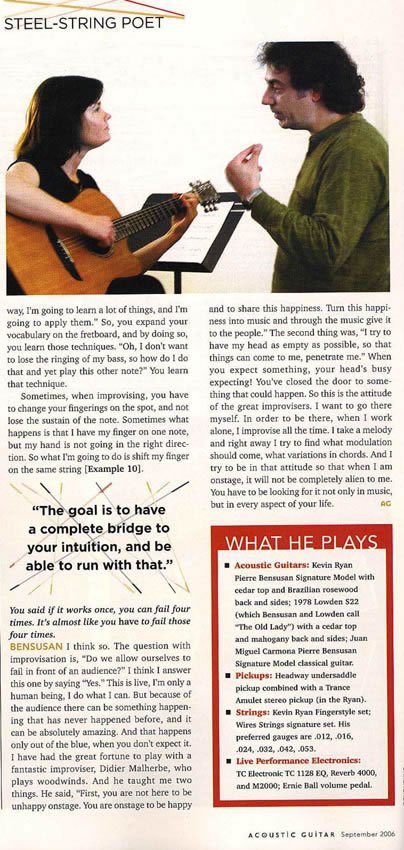

Bensusan shared his thoughts on technique, expression, the importance of listening, and improvisation before a sound check, a quick meal at a Pakistani restaurant, and a show in Berkeley, California.

How do you create the expressive, singing quality we hear in your music ?

BENSUSAN I don’t compose with my guitar. A lot of my ideas come from singing lines, listening to my internal chant, and following those ideas. They are not guitar-related. Some are extremely “downloadable” on the guitar. Some are not, and are very difficult to play. And they sound so easy when you listen to them, they sound so natural.

When I listen to “Hymn 11” (from Altiplanos), it’s obvious from the first note that I’m about to hear something very musical.

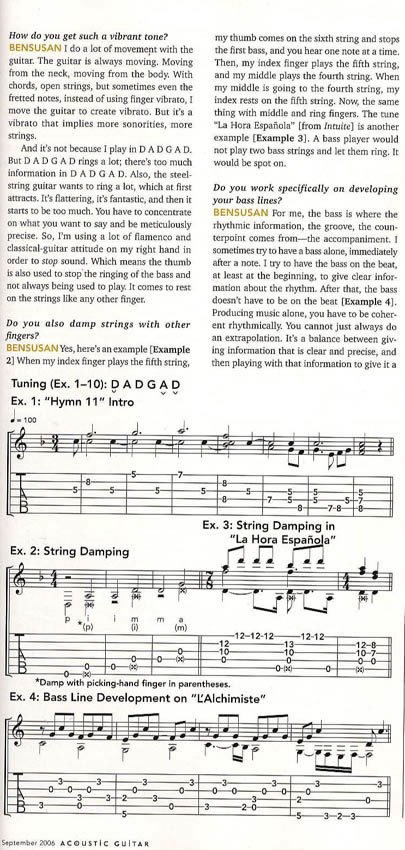

BENSUSAN I try always to reflect a musical universe, and to make that universe become storytelling or poetry: few words, lots of images, and different levels of meaning. With “Hymn 11” [Example 1], when I play the opening notes, it’s like, “OK, this guy is telling me something; what does he have to say?” In order to make the musical conversation come alive, you need to understand your instrument. At first, imagination is not instrument related. Then you use a tool—your guitar—to make this poetry concrete, and no longer abstract. You know, “Hymn 11” is one of my hardest pieces to play. And there are so few notes. It’s all a matter of sustain—the sustain of notes overlapping together, creating chords. There is the history of the note, and new things happening, with intensities coming from a very quiet place, and it goes up and up and up. This becomes storytelling. You are telling the story and you want to captivate your listeners and make them grow with the story.

Are there specific techniques you use to bring your music to life ?

BENSUSAN The first step in identifying what techniques are going to be required is listening. You may feel there should be vibrato, but it’s not there. And if it’s missing, you have to do something about it. But sometimes there is no need of vibrato. If you overplay the vibrato all the time, you kill the music. Because the music needs some things, and doesn’t need other things. So my attitude is, “Do the minimum, but do not fail to do the minimum.” And sometimes the minimum requires a lot.

How do you get such a vibrant tone ?

BENSUSAN I do a lot of movement with the guitar. The guitar is always moving. Moving from the neck, moving from the body. With chords, open strings, but sometimes even the fretted notes, instead of using finger vibrato, I move the guitar to create vibrato. But it’s a vibrato that implies more sonorities, more strings. And it’s not because I play in D A D G A D. But D A D G A D rings a lot; there’s too much information in D A D G A D. Also, the steel-string guitar wants to ring a lot, which at first attracts. It’s flattering, it’s fantastic, and then it starts to be too much. You have to concentrate on what you want to say and be meticulously precise. So, I’m using a lot of flamenco and classical-guitar attitude on my right hand in order to stop sound. Which means the thumb is also used to stop the ringing of the bass and not always being used to play. It comes to rest on the strings like any other finger.

Do you also damp strings with other fingers ?

BENSUSAN Yes, here’s an example [Example 2] When my index finger plays the fifth string, my thumb comes on the sixth string and stops the first bass, and you hear one note at a time. Then, my index finger plays the fifth string, and my middle plays the fourth string. When my middle is going to the fourth string, my index rests on the fifth string. Now, the same thing with middle and ring fingers. The tune “La Hora Española” [from Intuite] is another example [Example 3]. A bass player would not play two bass strings and let them ring. It would be spot on.

Do you work specifically on developing your bass lines ?

BENSUSAN For me, the bass is where the rhythmic information, the groove, the counterpoint comes from—the accompaniment. I sometimes try to have a bass alone, immediately after a note. I try to have the bass on the beat, at least at the beginning, to give clear information about the rhythm. After that, the bass doesn’t have to be on the beat [Example 4]. Producing music alone, you have to be coherent rhythmically. You cannot just always do an extrapolation. It’s a balance between giving information that is clear and precise, and then playing with that information to give it a distortion, a turn. That makes the flow entertaining and not predictable.

How do you create the harp-like effect used in many of your tunes ?

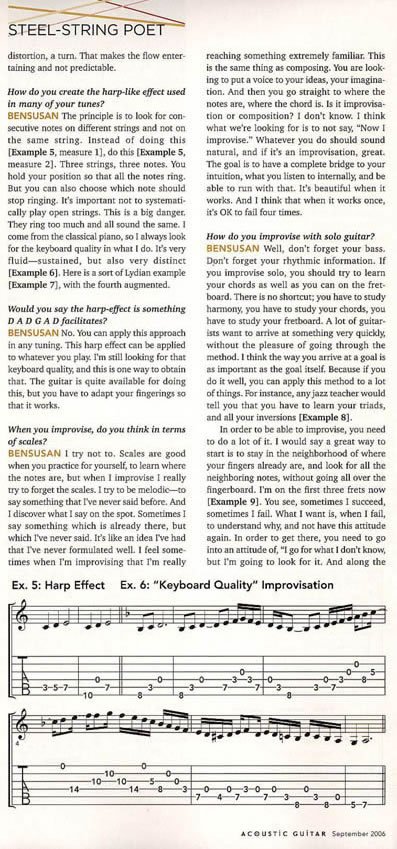

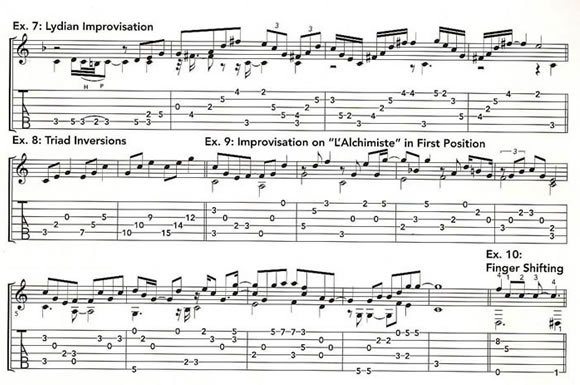

BENSUSAN The principle is to look for consecutive notes on different strings and not on the same string. Instead of doing this [Example 5, measure 1], do this [Example 5, measure 2]. Three strings, three notes. You hold your position so that all the notes ring. But you can also choose which note should stop ringing. It’s important not to systematically play open strings. This is a big danger. They ring too much and all sound the same. I come from the classical piano, so I always look for the keyboard quality in what I do. It’s very fluid—sustained, but also very distinct [Example 6]. Here is a sort of Lydian example [Example 7], with the fourth augmented.

Would you say the harp-effect is something D A D G A D facilitates ?

BENSUSAN No. You can apply this approach in any tuning. This harp effect can be applied to whatever you play. I’m still looking for that keyboard quality, and this is one way to obtain that. The guitar is quite available for doing this, but you have to adapt your fingerings so that it works.

When you improvise, do you think in terms of scales ?

BENSUSAN I try not to. Scales are good when you practice for yourself, to learn where the notes are, but when I improvise I really try to forget the scales. I try to be melodic—to say something that I’ve never said before. And I discover what I say on the spot. Sometimes I say something which is already there, but which I’ve never said. It’s like an idea I’ve had that I’ve never formulated well. I feel sometimes when I’m improvising that I’m really reaching something extremely familiar. This is the same thing as composing. You are looking to put a voice to your ideas, your imagination. And then you go straight to where the notes are, where the chord is. Is it improvisation or composition? I don’t know. I think what we’re looking for is to not say, “Now I improvise.” Whatever you do should sound natural, and if it’s an improvisation, great. The goal is to have a complete bridge to your intuition, what you listen to internally, and be able to run with that. It’s beautiful when it works. And I think that when it works once, it’s OK to fail four times.

How do you improvise with solo guitar ?

BENSUSAN Well, don’t forget your bass. Don’t forget your rhythmic information. If you improvise solo, you should try to learn your chords as well as you can on the fretboard. There is no shortcut; you have to study harmony, you have to study your chords, you have to study your fretboard. A lot of guitarists want to arrive at something very quickly, without the pleasure of going through the method. I think the way you arrive at a goal is as important as the goal itself. Because if you do it well, you can apply this method to a lot of things. For instance, any jazz teacher would tell you that you have to learn your triads, and all your inversions [Example 8].

In order to be able to improvise, you need to do a lot of it. I would say a great way to start is to stay in the neighborhood of where your fingers already are, and look for all the neighboring notes, without going all over the fingerboard. I’m on the first three frets now [Example 9]. You see, sometimes I succeed, sometimes I fail. What I want is, when I fail, to understand why, and not have this attitude again. In order to get there, you need to go into an attitude of, “I go for what I don’t know, but I’m going to look for it. And along the way, I’m going to learn a lot of things, and I’m going to apply them.” So, you expand your vocabulary on the fretboard, and by doing so, you learn those techniques. “Oh, I don’t want to lose the ringing of my bass, so how do I do that and yet play this other note?” You learn that technique.

Sometimes, when improvising, you have to change your fingerings on the spot, and not lose the sustain of the note. Sometimes what happens is that I have my finger on one note, but my hand is not going in the right direction. So what I’m going to do is shift my finger on the same string [Example 10].

You said if it works once, you can fail four times. It’s almost like you have to fail those four times.

BENSUSAN I think so. The question with improvisation is, “Do we allow ourselves to fail in front of an audience ?” I think I answer this one by saying “Yes.” This is live, I’m only a human being, I do what I can. But because of the audience there can be something happening that has never happened before, and it can be absolutely amazing. And that happens only out of the blue, when you don’t expect it. I have had the great fortune to play with a fantastic improviser, Didier Malherbe, who plays woodwinds. And he taught me two things. He said, “First, you are not here to be unhappy onstage. You are onstage to be happy and to share this happiness. Turn this happiness into music and through the music give it to the people.” The second thing was, “I try to have my head as empty as possible, so that things can come to me, penetrate me.” When you expect something, your head’s busy expecting! You’ve closed the door to something that could happen. So this is the attitude of the great improvisers. I want to go there myself. In order to be there, when I work alone, I improvise all the time. I take a melody and right away I try to find what modulation should come, what variations in chords. And I try to be in that attitude so that when I am onstage, it will not be completely alien to me. You have to be looking for it not only in music, but in every aspect of your life.

LISTENING COMES FIRST

Bensusan stresses the paramount need for any player first to be an attentive listener. “We have a lot on our hands when we play an instrument,” he says. “Sometimes we don’t listen and are too preoccupied with technique. We forget to listen to what we play. Only precise listening is going to help you choose which technique is good. It’s a pity sometimes to hear musicians who have a lot of musicality to express, but are just forgetting to listen to what they do. It’s amazing, the difference between someone who plays without listening, and then plays the same thing while listening. You see, when you listen, you are no longer alone: You are with the music. “You need to entertain. And I need to entertain myself; I am my first listener. I want to get a lot of pleasure from listening to the music that I am making. It’s a pain to learn how to play, but a pleasure to listen. This ratio between difficulty, working hard, and the pleasure of listening is very important to me. I play so the music can exist by itself and I can listen to it as if it were anybody playing. I can even say, ‘This is very beautiful.’ And I’m not referring to me—my ego—playing this music, I’m referring to what I hear. If I don’t think it is beautiful, I will say, ‘This is not beautiful.’ And then I try to find out why the music is not working.”

WHAT HE PLAYS

Acoustic Guitars:

* Kevin Ryan Pierre Bensusan Signature Model with cedar top and Brazilian rosewood back and sides;

* 1978 Lowden S22 (which Bensusan and Lowden call “The Old Lady”) with a cedar top and mahogany back and sides;

* Juan Miguel Carmona Pierre Bensusan Signature Model classical guitar.

* Pickups: Headway undersaddle pickup combined with a Trance Amulet stereo pickup (in the Ryan).

* Strings: Kevin Ryan Fingerstyle set; Wires Strings signature set. His preferred gauges are .012, .016, .024, .032, .042, .053.

* Live Performance Electronics:

TC Electronic TC 1128 EQ, Reverb 4000, and M2000; Ernie Ball volume pedal.

Nefertari

Music by Pierre Bensusan, from Altiplanos

“Nefertari,” Bensusan’s tribute to the famous Queen of Egypt, demonstrates many of the elements of his style: singing melodies, lush vibrato, syncopated bass lines, and challenging stretches. The tune alternates between 7/8 and 4/4 time, creating a strong groove with a sense of tension and release. You may find it helpful to learn the melody to the 7/8 section first (mostly steady 16th notes), then determine where the bass notes fall against the melody line. Holding all notes to their full values will help create the smooth, relaxed, jazz-influenced feel of this tune. You’ll need to pay careful attention to the indicated fingerings to achieve this. Be careful with the stretches, take your time and work up to them slowly to avoid injury. You may also find that using a capo at first makes some of the stretches less daunting.

—DOUG YOUNG

Press Release

From Acoustic Guitar, September 2006, issue 165, © 2006 String Letter Publishing, David A. Lusterman, Publisher. All rights reserved. For more information on Acoustic Guitar, contact String Letter Publishing, Inc., 255 West End Ave., San Rafael, CA 94901; telephone (415) 485-6946; fax (415) 485-0831; Website