Press Release

January 2014 ACOUSTIC GUITAR

Tuning In to the Creative Spirit

Fingerstyle guitarist Pierre Bensusan celebrates 40 years as a professional with a career-spanning live recording and signature-model Lowden. By Doug Young

It’s been 40 years since a 17-year-old Pierre Bensusan launched his professional musical career—not as a guitarist, but as a mandolin player in a bluegrass band. Bensusan was busking on the streets of Paris when he had an opportunity to join a bluegrass band led by legendary banjo player Bill Keith. But Keith already had a guitarist, so Bensusan joined as a mandolin player instead. Keith encouraged the young guitarist to start playing short solo sets on the guitar as part of the tour, and Bensusan soon found himself being booked as a solo guitarist.

Since then, Bensusan has become known as one of the world’s premier fingerstyle guitarists, combining dazzling technique with complex and adventurous compositions that incorporate elements of jazz, folk, and Celtic music as well as more exotic elements from his French-Algerian heritage. Although Bensusan tried various alternate tunings early in his career, he soon began to focus exclusively on D A D G A D, and his extensive exploration of that tuning’s potential has been a major force in its popularity. Although Bensusan has collaborated and recorded with other musicians, including saxophonist Didier Malherbe, he most often performs as a solo guitarist and vocalist. His eclectic, distinctive style has greatly influenced several generations of fingerstyle guitarists, but at the same time, his tone, phrasing, and melodic approach remain unmistakably unique.

To celebrate his 40th anniversary as a professional musician, Bensusan is releasing a three-volume live recording featuring performances that span his career. Titled Encore, the recordings include rare tracks from Bensusan’s stint playing mandolin with Keith, collaborations with keyboardist Jordan Rudess (of Dream Theater), and selections from Bensusan’s electronic looping days, but focuses largely on Bensusan’s virtuoso solo work. For listeners who only know of Bensusan from his studio recordings, the live release provides a look at the master fingerstyle guitarist’s highly improvisational approach to performance.

Bensusan is also collaborating with George Lowden of Lowden Guitars (also celebrating a 40-year anniversary) to create a new Pierre Bensusan Signature Model. Bensusan has been associated with Lowden and has performed with his cedar-topped S-22—which Bensusan affectionately calls the “old lady”—for much of the past four decades, only recently replacing it with a smaller-body signature model. The newest signature model should be available sometime in 2014. I met Bensusan during a break in a short US tour for a wide-ranging discussion about the new recording, his approach to improvisation and composition, and the importance of listening. Along the way, I was treated to some stunning examples of Bensusan’s mastery of D A D G A D tuning. As we began our conversation, Bensusan started to tune his guitar and paused to reflect. “There is something about tuning that we could talk about for hours. What do we tune? I was talking to my wife, and she said, ‘I think when we tune, we are tuning ourselves.’ Which, in a way, is exactly what it is. By tuning the guitar, you are tuning yourself with the ability to listen carefully to your pitch. This quality of listening is going to define the quality of your playing. If you don’t listen, it’s not going to happen for you.”

You’re known for the alternate tuning you use, D A D G A D. How does that influence your music?

The music I play is not because I play in D A D G A D. Of course, this tuning inspired me to certain approaches to the fretboard, certain things that came to my fingers. But the music I play is because I hear it, and very often it doesn’t have much to do with the guitar. Every instrument has a sort of fatal attraction—you know, what the instrument at first suggests. And so you go there, of course. You have to. But you have to move on until the moment where your inspiration—your imagination—takes over. It should be the thought that triggers your movements and efforts.

Does that mean you first imagine your songs when you are away from the guitar?

A tune that I play a lot is “L’Alchimiste.” This tune came to me by listening, not by using my fingers. I didn’t want to take the guitar too quickly and start playing what I was hearing inside. I needed to spend time with my inner sound, so that things made sense. Once I had a definite idea of the tune and where the music would go, that’s when I would take the guitar and start to elaborate on the song.

How concrete is the tune in your mind before you start to play it on the guitar?

Very often a lot of the song is already there. So I focus directly on how to play, instead of trying to find what to play. You know, “Oh, what can I find to play next?” It doesn’t work like that for me, and I’m happy and grateful that it doesn’t work like that. The time I spend looking for how to put ideas together is in my imagination. So my ideas are orchestral, counterpoint. I hear the bass line. I have a sense of where the harmony is going. Of course, it is when I pick up the guitar that all these things come together and I experience the do-ability of it.

There must be times when it is hard to play the ideas you come up with.

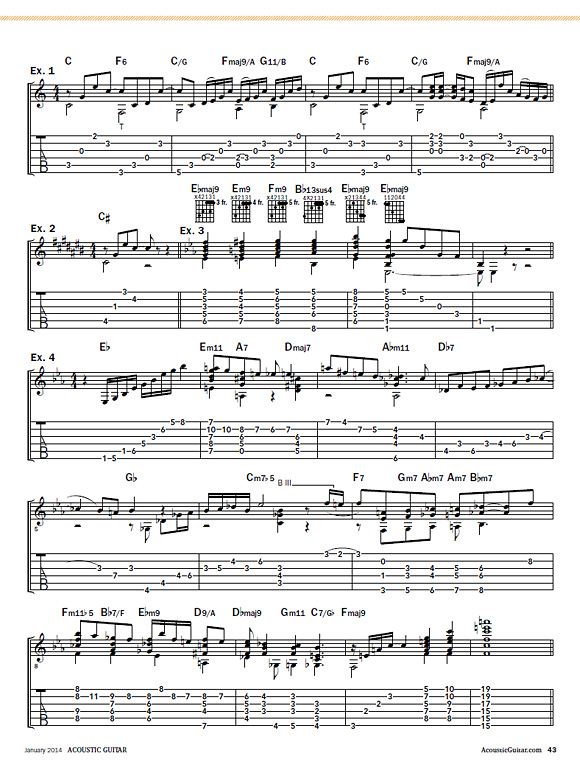

Sometimes it’s very easy, like “L’ Alchimiste” [Example 1]. The melody is like a folk song. The idea of playing in C is because it came to me in C. I always try to learn the piece in the pitch where it naturally came to me. It’s not a coincidence. The pitch is important. Of course, C# is nice, too [Example 2]. It’s very interesting to try different keys, especially keys where you have less open strings.

Many people think that D A D G A D is only for the key of D.

That is so wrong. How many keys are there [Example 3]? If you study the fretboard, it’s all there [Example 4].

Did you make a conscious effort to work through the chords in all the keys?

Well, I don’t pretend to know all the chords. I would not have time in my life to learn all the chords. In fact, a chord is just a coincidental interaction between several voicings.

Did you ever sit down with a chord book and just learn shapes?

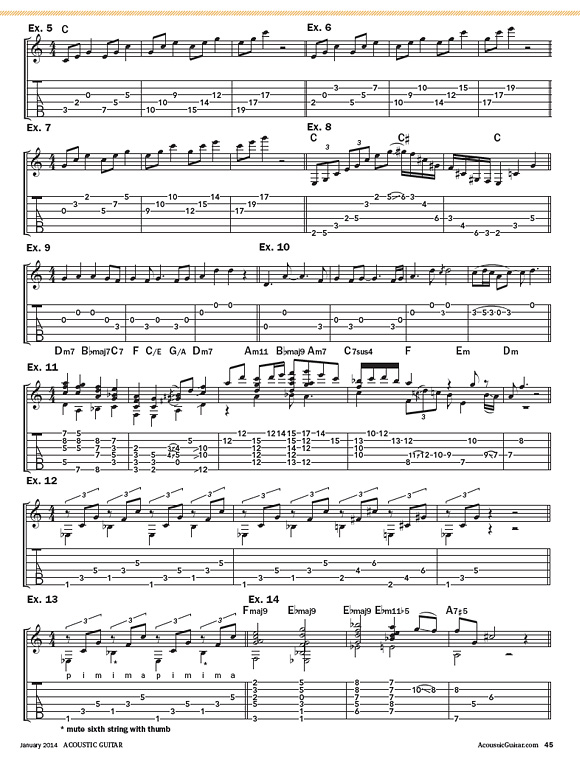

I did buy Ted Greene’s chord book [Chord Chemistry] at some point. I looked at one page, and I shut the book. I said, “Ted, I love you, but . . .” Because what is the point? I look at those books of chords as a little reminder once in a while, but basically I think we should learn chords on our own, by applying certain principles, such as looking for triads. That’s a great way to learn the fretboard, whatever the tuning [Examples 5, 6, and 7]. And then you can play arpeggios [Example 8]. All this time, there’s no D A D G A D involved. You just have the fretboard, and you have to work out the harmony. Sometimes people are very confused with open tunings. They think because they are in an open tuning, they don’t have to study the music. That’s a choice they can make, but it’s very limiting after a while.

If you don’t understand the fretboard, it’s like the tuning is driving instead of you. The tuning is driving. You’re having fun playing, rather than trying to make a statement. It’s not always fun to make a statement. It’s challenging. I’m writing a lot of music that often I don’t know how to play. It’s what I would like to hear. If I put a CD on, I would like to hear that tune. And if possible, since I had the idea, let’s try to have me play the tune. But basically, once this tune exists, it doesn’t need me anymore. Once a tune exists, why should it be played again? Why bother playing it again and again? Let’s move on.

How do you reconcile that with live performance? In concert, people want to hear you play your old tunes.

Good question. I might think, “Oh, no,” but then the music comes to me and says, “You are very wrong. You think every time you play me, you will play the same way? That you’re going to feel the same each time?” For me, it is difficult to play the same piece the same way every time. But even if you play the same notes, there are many ways to play the same notes. Here is a melody [Example 9]. Then you start interpreting the melody. You can start putting different value beats in the notes, different rhythmic values, so the phrasing is different [Example 10]. You can create a different sound. Especially with so many open strings, you can leave them vibrating— resonating. Or not. Then you can improvise through the chords [Example 11].

When you improvise like that, what is your thought process?

I just let myself listen, and think, “What about this?” or “Now we could hear that. Can I do it? Let’s try.”

Are you hearing a melody when you improvise? Or bass lines?

I’m hearing them as they come, and I also sometimes anticipate what will come. Sometimes I surprise myself, too. I try something, and I pray that it’s going to work. I may fall apart, and I accept that. If possible, not onstage in front of an audience, but it has happened

A common approach to improvising is to have a fixed chord progression, and improvise melody lines over it. But what you just played didn’t seem like there was that kind of predefined structure.

No, I never have predefined structures. I don’t believe in predefined structures. I think the music creates its own structure as it goes. You just have to understand the structure of what you are doing. There are as many structures as there are tunes. You don’t have to repeat something over and over, unless it is significant to repeat it and you can justify why you repeated it.

This is a different approach than, say, when you used a looper.

I had great fun with that stuff. For me, the looper helped me to elaborate ideas, different voicings, and to play very clean live. But the problem is that you become lazy, because you play one section with chords, then another section you improvise. What about playing it all together, like an orchestra? This is very challenging, and it’s also very interesting. What we do is not about the quantity, it’s about what we suggest. We do not have to play it all—it’s a big mistake to think it all has to be there.

So you create an illusion of many parts?

It’s more than an illusion. Everything doesn’t have to be there. The fact that it’s not there creates space, and music needs air in order for the notes to be important. If you play, play, play, there’s nothing left at the end for the person who is sharing the music with you.

Your live shows often seem to have a great flow. The energy builds as you go on. Do you plan the shows with a set list?

No. I know more or less the tunes, but I don’t write them down. I used to do that. But every so often, I’d see the set list, and say, “I don’t want to play that one now.” But I have to because it’s written down! And then I play it and it’s wrong. You have to play what feels right for you at the moment. When you decide that you are going to play something, it’s not the same as you played it last night. The mind frame of each concert is unique. Ultimately, it’s all about the music. How do we make the music as great as it could be, without interfering with it?

I have to build my confidence, too. I cannot start a set with something too demanding technically. It’s not because I cannot play it. I can play it at any time. But the beginning of the show is like, “Hi, my name’s Pierre, let me introduce myself.” I like to take people along gradually. And it’s important that I build my confidence, my relationship with the place, the sound, and the guitar. But I am warmed up. I play at least one to two hours before a show—during the soundcheck, in the dressing room. I like to be able to go to a place right at the beginning, to look for something and try to find it. That will give me confidence throughout the show.

What do you practice in those two hours? Are there exercises you do?

I do some things like [Example 12]. That’s some stretching. And with the right hand, I play thumb, index, middle [p, i, m] or, as soon as I play the second bass, I stop [the first] with my thumb, so that I give my ring finger a chance also [Example 13]. And then I try to play chords [Example 14]. I try to be fit physically, to not be in pain if I have to stretch. I prepare my tools, basically. I warm up my muscles so that I don’t hurt myself.

When you perform live, you improvise quite a lot, but your recordings are precise. It often feels like each note is selected with great care.

Before I write a piece, it has been going through a lot of improvisational phases. Once it’s written, it’s now time to record, and I want to make it as beautiful as it can be. The studio is one world, and live performance is another. This is why I’m so happy to start working on a live record. I’ve selected what I thought were the most genuine performances. And they’re far from perfect, but there are moments when I felt that the music was visiting me. When I was not ready—those moments are not on the record. But sometimes I’d choose a performance where even though one string was a bit out of tune, it should be there.

One thing I notice about your music is that your bass lines tend to be complex. You don’t use simple patterns like alternating bass.

You are talking about guitar! This is a confusion many people have. I’m not trying to play guitar. I love this instrument, and, of course, ultimately I am trying to play guitar, but I’m not trying to enter into any structure or style. I’m not interested in that. I have a manner of approaching music that is very personal.

The essentials are the melody, the harmony, the movement, rhythm, expression, and interpretation. At the end of the day, you make all the ingredients into a form that is abstract, with different layers. And the same tune can be played different ways. When you start changing the relationship between elements, you are creating a new piece every time—you are enlightening different aspects of it.

The bass has different functions. One is to give security to the rhythm. You give a tempo and a clear indication of what is going on rhythmically. Even nontempo music has a movement. No movement, no life. No life, no music. My bass is very rarely on the first beat. But it doesn’t need to be, because all of the elements of the tune contribute to give the real indication of where we are rhythmically. As long as we are there, every element can be in a different place, as long as they make sense all together.

It’s like with your voice. If you sing a cappella, you will sing differently every time, rhythmically. As long as you can do it with your voice, you can do it with the guitar.

So you’re not thinking mechanically, about where to put your fingers?

No, my fingers obey my desires, which are coming from my heart, how I feel. The fingers are like marionettes, and you are the guy holding the ropes. The problem is when people let their fingers take command. They are in their comfort zone, and they are not playing music. They are playing notes.

You need to have a lot of command over the instrument to make that happen.

Big time. But to me, virtuosity is not showing off what you can do on the guitar. Virtuosity is making the guitar and the musician completely transparent, and having the music just speak out. This is a high, high standard of virtuosity, for me. The music is using you as a channel. So you have to be ready for it. Technically, you have to really be ready. You work your ability, your tone. But when you play, all of this has to be forgotten.

The goal, then, is to be able to hear or feel something, and play whatever that is?

Hearing it in your head—it’s not enough. You have to go through the process of transforming it. This is the function of an artist. Musicians, writers, painters, actors—we are all transformers. We transform an idea into something tangible that can be seen or heard by other people.

Sometimes people start to tell the story of their life before playing a tune. You know, “I wrote this piece because of my grandmother. . . .” It’s too much information. Why do we need to know all that?

Transform your feelings about your grandmother into music. We won’t think of your grandmother when we hear it, but we don’t need to. Your grandmother was what triggered you to write the piece. You feed the music with your emotions, but what we hear is not your emotions—we hear them transformed.

DOUG YOUNG (dougyoungguitar.com) is a San Francisco Bay Area–based fingerstyle guitarist and contributing editor to Acoustic Guitar.

← Go back to previous page

← Go back to previous page